The child brides whom I encountered in different schools and communities during my fellowship are living examples of how patriarchal society subjugates women in the name of culture, reducing their identity to mere objects with no agency.

“You can talk about sanitation but don’t mention anything about menstrual hygiene,” is what the principal of a Government senior secondary school in Bikaner told me a few minutes before I was going to begin a session on gender sensitivity and health. I am posted in Bikaner as a Gandhi fellow under the Rajasthan Government’s Mission Buniyaad mission, which aimed to provide access to digital education to 10 lakh girl students in the state and was there to take a session as a part of the mission.

I was a little shocked when I heard the principal, not only due to what she said (after all, I was there to take a session about menstruation as a part of sanitation!) but also because just a day ago, she said she was totally fine with the session when I had told her about it. I did try to convince her to let me include the bit about menstruation, but she wasn’t convinced.

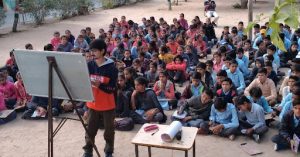

Me facilitating a Session on Gender Sensitivity at Govt. Senior Secondary School of Rajasthan

After conducting the session, I again tried to initiate a discussion with her to understand her reservations and what had made her change her mind. While I didn’t get a satisfactory response from her, another senior teacher posted at the same school told me that men usually don’t engage in issues related to women. He also told me that discussing sensitive topics like menstrual hygiene could in fact make things tougher for girls. Instead of showing the movie Padman to boys and girls together, as was instructed by the state government, he told me that the school administration only showed it to female students in the presence of female teachers.

Hearing such regressive words from a teacher really rattled me. But, due to this incident, I also got to know how deep-rooted and complex patriarchy is, how tough it was going to be to work on the issue related to women’s education in a state with the biggest gender divide in literacy and high rate of dropouts of females.

I remember it well how during my college days, I used to discuss with my friends the need to implement strict laws to combat regressive practices in our society. Working in Rajasthan and seeing the deep-rooted complex realities have made me realize that awareness programs hitting the patriarchal norms, authentic research before drafting a law, and monitoring of policies are deciding factors for how things will play out on the ground.

Joined the fellowship to get exposure on the ground

During the panel interview, I was asked by a senior member of the organization about my reason for wanting to work in the education domain and I told him that my reason was that I wanted to see positive change in society and that education was the only medium that could accomplish that.

When I was told that I’ll be sent to Rajasthan and will be a part of the state government’s project Mission Buniyaad, I got very excited and researched extensively about the state and its education structure.

I have been working as a Gandhi fellow in Bikaner Rajasthan for the past eight months now and have witnessed several incidents that show the ugly reality of the male-dominated society we live in.

This short journey has made me realize that researching on the internet and witnessing the reality of how things play out in real time are two completely different things.

I am not obviously completely denying the importance of education to bring about change, but seeing the power dynamics on the ground, I no longer feel that education alone is enough to bring radical change in our hierarchical society.

Having seen these realities so closely, I now feel that I was living in a bubble in the past, a topia of sorts, created by the same University campus that provided me an atmosphere in which I was able to acknowledge the privileges and prejudices I held, unlearn my bigotry, and helped me in transforming myself into a rational human.

“She has been married to a man because her uncle wanted to marry his sister.”

Ranvijay, who studies in Class X told me this when I asked him about a girl I saw in his classroom who was wearing a salwar kameez instead of a school uniform like the other students and had vermillion on her head. I was shocked after hearing that statement. He also told me that there were other girls like her in classes 9th and 11th who were married but who came to school in uniform.

The statue is a hope to 120+ Dalit families of Kapurisar Village

While facilitating my session on gender sensitivity and the importance of digital education in that school, the image of that little girl from 9th class kept playing in my mind. So, later, I visited her house and asked one of the elder family members about her marital status. He justified the practice by telling me that it’s a tradition and told me that the Gauna of the girl hadn’t been done yet. He also told me that the girl would only be sent to live with her husband once she would legally not be a minor.

This girl and other child brides like her whom I encountered in different schools and communities during my fellowship are living examples of how patriarchal society subjugates women in the name of culture, reducing their identity to mere objects with no individual agency.

Although I knew that working in the remote villages of Rajasthan was going to be tough, the constant failures and arguments with some stakeholders In the initial months of the fellowship program increased my pessimism. To be honest, I wasn’t mentally prepared to witness and face such normalization of casteism and patriarchy as I saw.

Yet, some things also give me hope. For example, when I was in this pessimistic phase where I was questioning everything, I met a boy during one of my school visits. He showed his hand to me and told me that he had written all the women’s helpline numbers that I had mentioned during the session. He told me that if he ever sees any kind of injustice happening to a woman around him, he’ll use these numbers to register complaints.

The kid from Kapurisar village who wrote the women helpline number on his hand and showed it to me after the session.

I don’t know how serious the boy was about what he said, but that little conversation helped me find the optimism that was fading away. It made me realize the journey to achieve an egalitarian world is long and I have to keep doing whatever I can to support people facing oppression on a daily basis because of their identities.

This also reminded me of how much I believe in Angela Davis’s quote, “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.”